WH&Y authors: The Conversation

Photo by Caitlin Venerussi on Unsplash

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Authors: Tracy Evans-Whipp, Australian Institute of Family Studies and Constantine Gasser, Australian Institute of Family Studies

Teenagers who have at least one close friendship are better able to bounce back from stress. This is one of the latest findings from the Growing Up In Australia study.

Growing Up in Australia has been following the lives of around 10,000 children since 2004. In 2016, the older children in the study were aged 16–17. We asked them about aspects of their lives including their peers, school environment and mental health.

One aspect of teen well-being we looked at was resilience. This is the ability to bounce back from stressful life events and learn and grow from them.

Stressful life events may include arguments with friends, sporting losses and disappointing test results. A more serious setback may be family breakdown, the illnesses or death of a family member, or being the victim of bullying.

Overall, teens said they displayed characteristics of resilience often, but boys significantly more so than girls. Our findings also show a strong relationship between not having a close friend and a low resilience score

Boys more resilient than girls

Research suggests a person’s resilience is determined by a variety of factors. These include individual biological and psychological characteristics, relationships with family and peers, and environmental influences such as those in the school and broader community.

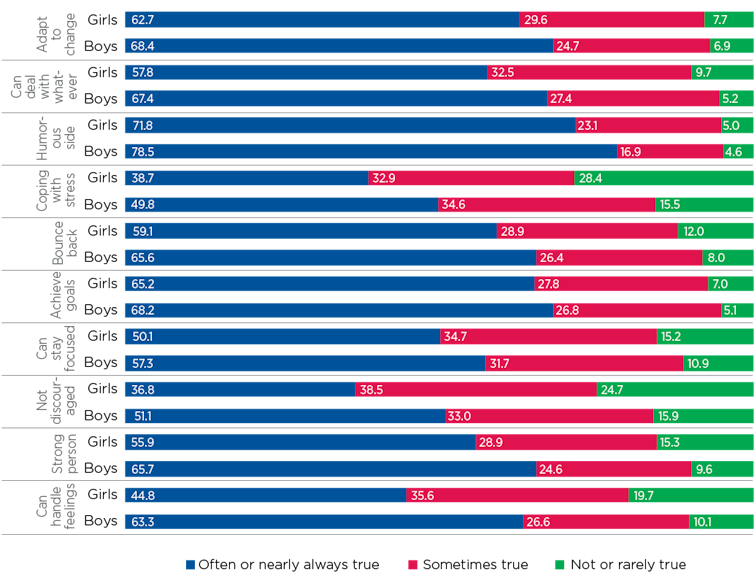

Our study asked teens to rate themselves on ten different aspects of resilience including their ability to adapt to change, how well they can achieve goals despite obstacles and how easily they are discouraged by failure. Together these gave a score from 0 to 40 (the higher the score, the higher the resilience).

The average total resilience score for adolescents was 26.5 out of 40. This suggests the “average” 16–17 year old views themselves as displaying resilient characteristics often.

Boys had significantly higher resilience scores than girls – 27.6 out of 40 for boys compared to 25.5 for girls. For example:

-

51% of boys and 37% of girls said they were not easily discouraged by failure

-

63% of boys and 45% of girls said they can usually handle unpleasant feelings

-

50% of boys and 39% of girls responded “often or nearly always true” to the statement “coping with stress can strengthen me”

-

67% of boys and 58% of girls felt they could (often or always) deal with whatever comes.

It is possible that when answering the survey questions boys may be more likely to want to appear strong in the face of stress than girls. But other studies have also shown significantly higher levels of resilience in boys.

Close relationships make kids stronger

We also looked at how supportive environments – such as family, school community and friends – affected teens’ resilience.

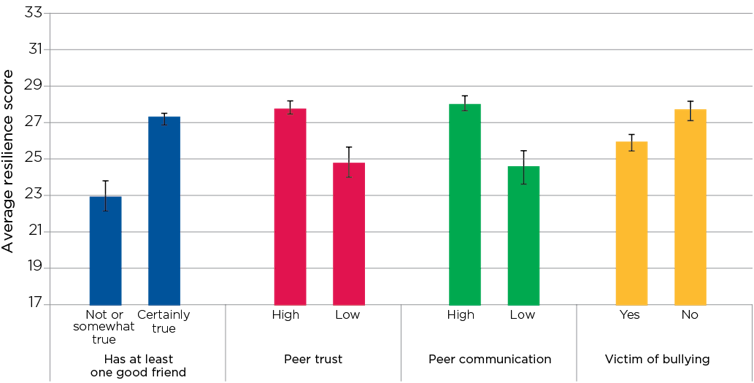

Of the 16–17 year olds we interviewed, 84% said they had at least one good friend. These teens had average resilience scores of 27, compared to 23 for the 16% who said they did not have a good friend (this is a statistically significant difference).

We also found the nature of the friendship important. Average resilience scores were higher for teenagers who had

-

high levels of trust in their friends — average resilience scores were three points higher than for those with low levels of trust

-

good communication with their friends — average resilience scores were 3.5 points higher, compared to those who reported poorer communication.

The flipside to having a close friend is being a victim of bullying. The average resilience scores of teens who had been bullied in the previous 12 months were almost two points lower than those who had not.

But even the harmful experience of being bullied is not as damaging to teens’ resilience as not having a close friend to confide in. A good friend raised average resilience scores by four points.

We also found teens who felt close to their parents and other family members had higher resilience.

Around 16% of young people lacked family support consistently through their early adolescent years (10–13 years old) and these teens reported significantly lower resilience levels at age 16–17.

Lacking family support means a teen doesn’t have people in their immediate or extended family who they trust when they want to talk about things that upset or worried them.

The average resilience score at age 16–17 for those who lacked family support in early or mid-adolescence was 25.3, compared to 26.8 for those who had support at one or both ages.

Our findings do not demonstrate a causal relationship between friendship and resilience. Because teens reported on friendships and resilience at the same time, it was not possible to tell whether those who have no close friends were so because they were less resilient, or whether they were less resilient because they had no close friends.

But our findings do highlight the vulnerability of teenagers lacking close relationships.

Resilience can change as people interact with and respond to other people in their lives and their environments. This creates opportunities to promote resilience in young people in different settings.

For anyone caring for or working with teens, a key finding from our research is that one of the best things you can do to foster resilience in a young person is to help them find and make friends. One good friend can make a big difference.![]()

Tracy Evans-Whipp, Research Fellow, Australian Institute of Family Studies and Constantine Gasser, Senior Research Officer, Australian Institute of Family Studies

About The Authors

The Conversation

The Conversation is an independent source of news and views, sourced from the academic and resea...